Mourning is Broken Once Grief Erodes

Two years after the death of his father, Mark Cantrell shares this personal essay to mark the anniversary and celebrate a life lived

GRIEF is a peculiar thing; seeming to have a life of its own.

Like water, it finds its own level; seeps into every tiny crack, batters down defences, and makes its way out in unexpected places.

Going further, this is water with currents; eddies and layers, convoluted and folded in a three-dimensional fluidity of emotion. A sculpture, forever in motion, if you will.

Grieving has its own scent and flavour, too; sourced in the ingredients of time and memory and feeling, dissolved in its restless medium.

But in waxing lyrical, here, I’m kind of avoiding the point; so, no more purple essence.

Clarity of Time

My father’s death is not so fresh as it was, now. Months have elapsed since he passed [at the time of writing]. I find myself in a position to take stock; rather, I should say, worn thin the excuses for procrastination.

What I recall with most clarity is the sense that my father’s death hit me harder than my mother’s demise, many years earlier. If that sounds heartless, hear me out. It’s that observation that prompted these musings.

My mother lingered. Death was a protracted process that took days, weeks, months even. That last breath, when it arrived, and then slipped away with her, came as a mercy. It was a release – and a relief – from a cruel condition, as much for my mother as it was for her children holding vigil1.

My father’s ending was, by contrast, more or less a sudden affair. Right until near the end, he was an active old codger. In a sense, it was that mobility, combined with his dementia, that did for him. But the day he was ushered into Death’s reception room began much the same as any other. Not that we understood it in those terms; not then.

No, Death came at us sideways, out of the blue; laying claim to my father before ever we had the chance – unlike with my mother – to recalibrate our sense of time and mortality.

Carnage in the Cortex of Being

THE end of my mother’s life came in June 2008, but the beginning of that terminal journey began three years earlier, when she had a stroke; a bad one.

Quite how much of the person that was my mother remained, after the blood vessel detonated such carnage in her cortex, I can’t truthfully say. There was recognition in her eyes, and a familiarity expressed in her mannerisms, at least; certainly, in the early months, post ‘recovery’. After that, who knows?

What was left of her continued to unravel, as an already damaged brain succumbed to the erosion of dementia. My mother was already unable to express much of anything, still less seek solace in our company from whatever ‘ghosts’ haunted her waking moments; dementia only made it worse.

Whatever they were, these spectral inner visitations, they were to become a source of profound distress. That was, perhaps, the worst thing about the whole sorry condition.

We were helpless onlookers. She’d gone beyond our reach, but not so far that she’d left us behind in the realm of the mortal. There was nothing we could do to set her fractured mind at ease, to exorcise those ghosts, or to connect with the fragments of being locked away in a cranial tomb. She was a haunting, haunted.

The stroke left her crippled; all the classic symptoms. I forget the side now, but she was blind in one eye, deaf in one ear, unable to move that side of her body. Her arm and fist remained clutched to her chest thereafter.

The damage also robbed her of speech, and much of her ability to swallow. Once articulate, and fond of penning the odd poem, her speech became little more than the odd word, the names of long-vanished acquaintances, short but garbled utterances that conveyed the presence of structure and syntax, but a meaning – if there was one – that was scrambled beyond cognition.

Sometimes, my mother would wave at someone at the foot of her hospital bed; there was nobody there. Some ‘ghost’ incarnated from memory and transposed on the real, perhaps; a waking dream, some hallucinatory visitation? We couldn’t say.

In the beginning, it was benign. If only it had remained so. As time wore on, as the weave of her damaged cortex continued to unravel, whatever phantoms my mother perceived only became a source of torment.

The truth is, it’s impossible to say what she was experiencing. She couldn’t communicate; we had no means to grasp any sense of her situation. She was locked in; we were locked out. Sure, we could surmise, but it was projection, nothing else; pure speculation, fed with the thinnest of gruel.

All we could do was witness the outward expressions of her inner torment. And if my mother was in distress, it was distressing for us to watch too.

As time wore on, screaming episodes became common. My mother would wail and cry out; shouting at things only she could see. There was fear in her face. There wasn’t a damn thing we could do to soothe these fits of horror.

Home is Where the Heart Is

MY dad was my mother’s primary carer, once she returned home from residential care. He’d been adamant about bringing her home, and bore the burden come what may.

We – their son and daughters – ‘hovered’ in the background, providing whatever support we could, as and when required.

Whenever these screaming episodes took place, he was the only one able to calm her down. The only one. Sometimes these episodes were in the dead of night, so he took to sleeping with her in the hospital bed that had been assembled in the living room.

The two of them squeezed together in a bed made for one; it must have taken a toll on his own constitution. But you’d never know from his behaviour; never a word of complaint.

My dad would soothe her, feed her the paste that formed her meals, move her from bed to chair to toilet at need (sometimes with my assistance); kept her company, kept her home.

Carers came in on a regular schedule. They cleaned my mother, changed her clothes and bedding; checked and maintained her catheter and adult nappies. They’d make a fuss of her, and brush her hair; she enjoyed that. You could tell. It was the one sliver of silver.

‘Till Death Us Do Part

FAST forward to the end days in hospital, my mother already looking horribly dead even while she still lived; the several false alarms that she was ‘finally’ slipping away, only for her to hang on for another day, another night. Emotionally wearing, that; numbing even.

Finally, the last day; irrevocable. My dad held her, wailing for all he was worth (I’d never seen him so emotionally distraught). And then, after fading away over hours, my mother was finally gone.

The physical change was striking and hard to quite capture in words. If I were religious – or felt like being poetic – I might say I’d witnessed the very moment the soul exited the flesh.

My secular mind interprets the process in physical terms: the relaxation of tension in the micro-muscles of skin and face, the dissipation of latent pressure with the last dribbles of flowing blood. Whatever, there was a clear shift from living being to inanimate organic matter.

Does that sound cold? When you’re caught in a tangle of exhausted emotions, perhaps solace is sometimes to be found in the realms of the dispassionate.

But, amidst all the heart-wrench of the day, the sense that she was finally free was palpable. With that, for sure, comes a sense of relief and release. My mum’s suffering was over: she was finally at peace.

To the Boy, a Man

THE Reaper came for my dad nigh on 15 years later. By then, dementia had whittled him away and I was his full-time, unpaid carer. Unlike my mother, though, he never suffered.

My dad had vascular dementia. Like my mother before him, his decline began with a stroke, albeit a ‘minor’ one (in the scheme of things). He told us the tale of how he’d fallen over at home, lost his sight briefly; he described it as the “shutters coming down”, but it passed, and he got on with his day.

We took the tale as he offered it: as just a story, a retelling of a curious incident. There was some concern, of course, but it was tempered by the fact he’d picked himself up and got on with his day, no apparent harm done. Over the next few weeks, however, an abrupt change made its presence clear.

We all forget things, especially – the expectation goes – as we get older. My dad had become forgetful. Little things. Oddities. At first, we joked about it. Eventually, humour gave way to worry. We made him an appointment to see the doctor.

Typically, he didn’t see what the fuss was all about, but he went along with it; the tests, the scans, the questions. There, in the image of his brain, the doctors discovered the lesions left over from his ‘fall’; tell-tale scarring that gave evidence to the stroke that had set the rot in his memory.

Back then, he remained competent and capable of handing his affairs, but the direction of travel was set in stone – or, rather, the grey matter. Decline was inevitable. If he ever felt fearful of dementia’s encroachment, or frustrated at his loss of memory and the erosion of his capabilities, he kept it to himself. That’s just the way he was.

By the time he was nearing the end, there was little left of him; just this – impression – of a very small child2. The memories of his life, family, friends and acquaintances had all but evaporated.

Picture a block of dry ice – carbon dioxide frozen solid. It doesn’t melt. As the dry ice warms, it sublimates. That is, it goes from solid straight to a gaseous state.

A block of dry ice in a room temperature environment releases its own shroud of mist, diminishing as it goes, until nothing remains but invisible gas.

That’s how I envisioned my dad’s dementia; his mind sublimating, memory and cognition wisping away to blend into invisible oblivion. Until, eventually, there was just a nub of him left.

Face of a Stranger

THERE are all kinds of ways his dissolution might be conveyed, but they’d form essays all of their own, so let’s stick to the family photographs on the wall. As the years passed, and the dementia ate away more of his soul, the faces in those images faded from recollection.

There came a time when he no longer recognised his late wife, Edith. Even the knowing that he’d been married vanished. With it went any memory of the grief that once wrenched out such wounded bawling as he held my mother during her final hours.

A mercy, maybe? It’s one way to look at it. A strange mercy, though, that eases the hurt by erasing the love that bore it. No, it was just another twist of a cruel condition.

The rest of us soon vanished, too; his children, his grandchildren, the very notion that we’d ever existed at all. The faces on the wall were strangers. Towards the end, the only face he knew was that of his father; over a century old, a colourised photo of Jacob Henry Cantrell in his First World War army uniform.

Even that was beginning to fade. My dad was slipping out of time and space and memory. Yet, to the very end, he’d remember his sister, Dorothy. There were 18 months between them. They’d always been close. She was the eldest. Their two younger siblings had passed years before, already forgotten, but some fragment of recollection for his oldest sibling remained.

“I must go see Dorothy,” he often said, out of the blue; once even grabbing his jacket and putting it on. Even on his death bed, among the last of his utterings, was the odd reference to seeing his big sister.

By then, he was utterly unaware that she lived not far away, in a care home, locked away by dementia in the darkness of her own faded mind. Bed-bound, she was; largely uncommunicative, seemingly unaware of visitors and surroundings. It was terrible to see this once stalwart Yorkshire lass reduced to such a state.

She died some six months after her brother; unaware – and no longer capable of comprehending – that he wasn’t around to mourn her.

As for me, my dad had no idea I was his son. Curiously, though, he’d make the odd reference to “my lad, Mark”, which kind of contradicts the notion that he had no recollection of ever having children, but there is no sense in dementia.

No doubt my sisters might feel aggrieved at that, but then it was surely a side-effect of my constant proximity as his unpaid carer. I was a familiar presence, but ever the eternal stranger.

Little remained of Peter Cantrell in those days. Just a name. But there was enough of a spark in there that he was still a person, albeit one detached from past and future tense to occupy an eternal present. He was happy in his little world, though.

In a way – a very real and profound way – our roles had reversed. That impression I frequently gained of a small child may not have been an entirely accurate reflection, but even so I had become the dad, and he the dependent son.

My dad’s demise was 10 years in the dying, you might say; he died a little bit every day with that erosion of being, until all that remained – more or less – was this singularity of a child, held in an eternal event horizon of a present moment.

There he remained, suspended between two abyssal oblivions – one, the darkness of annihilated memory; the other the erasure of death – until some external happenstance pitched him into the finality of the latter.

When the Time Comes

ALONGSIDE his dementia, my father had COPD – a legacy of smoking from the age of 11 – dodgy plumbing, unreliable bowels, fragile bones, and no appetite to speak of3, but he remained active to the end.

I often joked he was on his feet more than me. Sure, he was getting doddery on his legs, but he could still handle the stairs, though I made sure to escort him up and down; just in case.

All in all, not bad going for a man who’d been born at home, premature, in pre-NHS times, and who wasn’t expected to survive. The story goes, they called the local Catholic priest to give the newborn Peter his Last Rites.

The priest took Peter’s little and hand in his, felt the grip, and declared solemnly: “The boy is strong. He will live.”

And live he did – to the ripe old age of 96. He managed a span that went beyond those attained by his parents, and all his siblings, with the exception of Dorothy, and doubtless beyond the expectations of the era of his youth. But, then, he was always a bit of an outlier and contrarian, my dad.

Will we, his children and grandchildren, live to such a great age? Personally, I have my doubts, because the social conditions prevalent in his infant years have returned with a vengeance.

My dad was born in a Britain rife with poverty and inequality. Poor housing, no public healthcare, little in the way of a meaningful social security safety net; those were the order of the day. And Bradford, in those days, was still a sooty, industrial city of ‘dark, satanic mills’.

He became an adult just in time to be called up for armed service in the tail end of the Second World War; he missed the fighting by the skin of his teeth. Victory in Europe was declared merely days before he’d been due to ship out. Instead of war, he served his time as part of the Allied occupation of post-war Germany.

When his time was up, he returned home to a Britain that was intent on changing things for the better for ordinary working class people. The National Health Service was instituted, a housebuilding boom with the large-scale construction of council housing, the instigation of the Welfare State; a system of social security to alleviate, if not entirely eradicate, destitution and poverty.

That was then. This is now. Britain has been pushed backwards. Over the last 40 years or so, an ‘unholy alliance’ of Conservative and Labour governments has worked tirelessly to uproot the gains that war-time generation wrested from the hands of the wealthy and the privileged: a National Health Service on its knees; a Welfare State retasked not to alleviate poverty, but to enforce it and push people deeper into its mire; a crushing housing crisis, bringing with it a resurgence of gruelling slum conditions.

These are Dickensian times to say the least. We could go on, but that would be an essay – and more – in itself. Suffice to say, my dad returned to ‘civvie street’ in a country far more conducive to a long and fruitful life, than the one that has since been created in its stead, but that’s enough digression.

End of Days

THE beginning of my dad’s end came in February 2023. In a way, it was his very mobility that did for him; in another, the inactivity bourne of a hospital bed. The two conspired to shuffle him off this mortal coil.

Sure, I was aware mortality could strike at any time. We all come with an expiry date, even if we don’t generally know when it is; much the same can be said of the elderly. We know it’s coming; we don’t know when, or necessarily the how.

Falls are among the biggest killers of the elderly, whether they remain compos mentis or not. The tumble isn’t necessarily the killer, though; rather, it’s the resulting infirmity that puts them on the slippery slope to decline.

Sooner or later, my dad was going to suffer a fall that ultimately killed him. If not that day, then the next, a week later, a month hence, a year even; it just happened to be that fateful morning.

As it was, the day began much like any other. I got my dad out of bed, up and dressed; escorted him down the stairs. I put the telly on for some background ambience. Then I warmed him a teacake in the microwave (he liked such treats). Once he had his munchie, I left him to potter around in the living room while I made him a cup of tea.

Just another day; much the same as any other during my three-year stint as his full-time carer. A godawful bang put paid to that. The commode slid along the floor and came to a halt by the entrance to the kitchen.

“What the ffff… was that?!”

My heart was in my mouth. I found him on the floor by the window, struggling to get up. Obviously, he hit the commode on the way down, sent it flying.

Somehow I managed to help him up (he’s heavier than he looks), supported him to the couch, and got him sat down. He seemed more bewildered than hurt. I’ll never forget the way he clutched the teacake when I gave it back to him; like a small boy who’s had a bad scare grasping at a crumb of comfort.

Otherwise, he seemed fine; shook up, but uninjured. I checked him over, of course; looked for telltale bumps and bruises, but it seemed we’d had a lucky escape. Normality began to resume.

As the day wore on, however, it became evident that things weren’t right. My dad wouldn’t – couldn’t – move from the couch, but there was still no sign of injury. The situation was a mystery.

This isn’t the place to explore all the gory details4, so instead let’s kind of cut to the chase. A 999 call for the paramedics; a few hours waiting, a late-night hospital admission. None of us, as yet, any the wiser.

Ironically, it was my dad’s heart that got him admitted to the hospital. Not the fall. The paramedics found an irregularity in his ECG that meant they were required to take him in; a routine precaution. Hours in A&E followed, a succession of doctors and nurses. Finally, following a bit of physio to restore his confidence after the fall, it was decided that was fit for discharge the next day.

Over night, he vomited; I got the call early the next morning. The doctors were worried he’d taken some of the vomit into his lungs.

My dad wasn’t coming home any time soon, then. Instead, he was moved to a ward. More tests and scans. He was given powerful antibiotics to combat infection in his emphysema-damaged lungs.

The prognosis was poor, but not yet certain, the doctors said. There was a chance of him making it through, if slight. In such circumstances you do the only thing you can: try to prepare yourself for the worst, hope for the best.

Like the medical staff, we were horribly aware that the situation was dire: hospital is not the ideal place for someone of my dad’s age and general condition, but given the risks posed by the aspirated vomit, there was no other choice. Fate plays a cruel game.

In the midst of all this, that’s when the mystery of my dad’s immobility was finally resolved. X-rays taken to assess his lungs revealed the horrible truth. When my dad fell – and slammed into that commode on the way down – he broke five ribs. One of them was broken in two places.

Even then, there was no outward sign of any injury. That was the weird thing. My dad’s age and medications had left him with thin and delicate skin. He bruised extremely easily, but there had been no sign of any bruising.

Eventually, after the x-ray – it’s secret out, you might say – a massive bruise did finally blossom on the afflicted side of his chest.

By then, of course, it was all moot. The fall didn’t kill him, so much as create the conditions for mortality to take root.

Over the next week or so, my dad responded well to treatment, but his dementia took no holiday. Had he been a little less advanced in the condition, he might have survived to return home and pootle around the living room as before.

Sadly, the inactivity from being confined to bed, combined with a lack of stimulation, and little in the way of oral nourishment, atrophied his ability to swallow. Food or drink had as much likelihood to gurgle its way into his lungs, as his stomach, not that he had much of any appetite remaining.

This was the doom – my sisters and I – had been dreading. As the doctors advised, and as we clearly understood, the only route now was palliative care. My watch was ending.

There was one thing we could do for our father, though: bring him home. We hadn’t been able to do that for our mother, but we could see to it that out dad spent his final days in the comfort of familiar surroundings. So that’s what we did.

The end is nigh, now. Compared to my mum, there was barely any gap between the catastrophic event that set mortality in motion, and the final passing of my father from life. Weeks, not years; barely any time at all to come to terms with the reality of the matter.

Final Sleep

MY father had a peaceful – dare I say relaxed? – death. When he breathed his last, it was just like he was still just sleeping. Indeed, we weren’t certain he’d actually gone.

There we were, standing around my father’s bed, watching, wondering. We knew his time was up from the change in his breathing, but was he still, albeit too shallow for us to see; would he take one more – final – breath?

Minutes ticked by; we stood vigil. More minutes; we begin to feel foolish, but still uncertain. Eventually, we make the call. The paramedics arrived in rapid time and confirmed the finality of the occasion. Our dad was gone.

Still, seeing him lying there under the duvet, head perched on the pillow, it was hard to shake the expectation that he might stir, raise his head to look at us, and mutter something; as he often did.

During those last couple of weeks or so that he was back home, he slept a lot. There were plenty of wakeful periods, though these became less frequent as the final day approached.

We tried to feed him; little more than the odd chocolate button. He’d take no more. We’d try to keep him hydrated, a sip of Ensure or tea, or just water, in a little shot glass. Sometimes, he’d handle the glass himself; mostly, we helped him take a sip. Token efforts, that’s all. For comfort’s sake, really.

Conversation was as limited as his ability to take nourishment, but still we talked (best you can, what with the dementia).

In those last days, as we kept vigil, my sister told me that on more than on occasion, while I was elsewhere doing day-to-day chores, he’d asked for me. It threw me a bit, hearing this, I must confess. Was my dad’s memory having on last spring, I wondered? Certainly, it suggested he’d recalled who I was, at long last.

During those last conversations, the things he said often didn’t make sense. They seldom did, given the dementia. We’ve had many a nonsense conversation, my dad and me, over the years. Sometimes that’s just how they panned out; other times, I just went with the flow and let my verbiage play.

The thing is, he was still very much articulate; he could string a sentence together that made perfect sense within its own parameters. It had structure; syntax, grammar, the words fitting appropriately together. It just didn’t necessarily have any connection to the situation, or whatever was said to prompt his reply.

When you think about it, really think, even a brain as diminished by dementia as was my dad’s is capable of remarkable feats. If you consider the magnitude of processing power it takes to achieve even the simplest of actions: to just stand, or walk; to assemble a sentence and vocalise it; to pick up and manipulate a cup to our lips; to simply pull on a pair of pants.

We think nothing of such things; until we witness the unravelling of the complicated neural machinery that makes such miracles possible.

The brain is a remarkable organ, even when damaged. We take our grey matter for granted, but that clump of fatty tissue is us. It makes possible everything we are, everything we do, from the simple act of scratching our arse, to changing a TV channel, from asking the time of day, to composing a symphony, penning a poem, or cracking open the secrets of the universe.

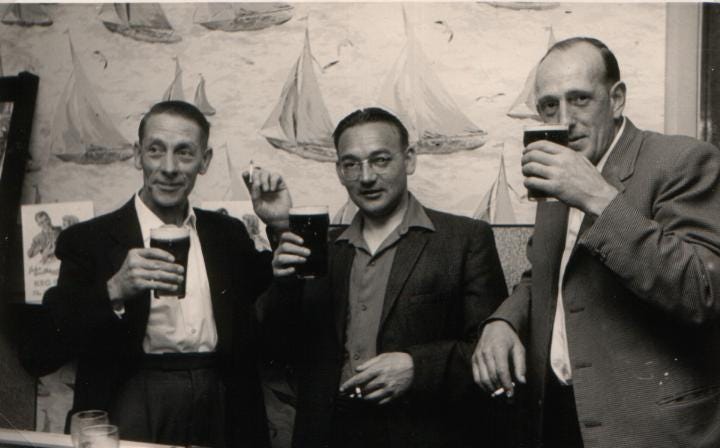

My dad wasn’t one for the latter; wasn’t much for poetry or music or much of a reader, for that matter5. He liked his football; he followed the news, he had a healthy disregard of politicians. He liked to work with his hands; a committed DIYer. He liked a pint, and shooting the breeze with his mates at his local. All of that, now, washed away like tears in the rain (to borrow a line).

In those last days, during my dad’s wakeful moments, he remained as lucid and engaged as dementia allowed. That is, he was there with us; he was aware of his surroundings. Garbled though his speech may have been at times, some of the things he said left me with an inescapable sense that he was making his goodbyes.

We never got to say goodbye to my mum, at least that’s how it feels. Sure, we could stand there at her bedside and mouth the words, but she’d gone beyond them. The situation offered no means to sense any kind of mutual farewell; unlike with my dad. With him, there was a sense of closure; not release.

You’d think that would leave less of an impact; the lack of any sense of closure with my mother really ought to leave the deeper scar, surely? But then, as I said, my mother’s passing was a gruelling affair. At the end of it was the relief to see her suffering no more.

My father, by contrast, wasn’t – hadn’t – suffered; was enjoying his life, however diminished it had become. There was a much stronger sense of loss, for that, if that makes sense; one that served to leave a deeper mark.

For me, in the thick of it as his day-to-day carer, my dad’s demise feels almost like a personal failure. The end was inevitable, of course. It was just a matter of time. I know this. All the same, it still feels as if I failed to protect a small, defenceless child. That ‘small boy’ suffered a catastrophic fall on my watch; that fall ushered the ‘child’ into the grave.

In that sense, I failed to protect him against something that comes to us all, in the end; the hole he leaves behind is deeper for that.

Yes, it’s a daft notion, I know, but it’s a relic of his – our – condition. I spent a long time in the company of dementia; it surely left its mark.

MC

Copyright © January 2024. All Rights Reserved. Originally published on Mark Cantrell, Author on 17 March 2024.

NOTES:

1 Although I do not – and cannot – speak for anyone here but myself.

2 Albeit one convinced of his own adult capability to look after himself.

3 Without nutrient drinks – Ensure, Complan – he would have starved to death years ago; he wouldn’t eat anything more than a few biscuits, the odd mouthful of cake. Strangely, about 10 months before his death his appetite returned. Suddenly he was eating proper food, actual meals. It took a few weeks for me to grasp the change, though. Some of the clues were mundane; I’d find half consumed tins of beans lying around. Others were pretty grim; I’d catch him eating food waste (and more grotesque things) out of the kitchen bin.

4 I wrote about it here.

5 Although he did like to sing; he had quite a good voice, insofar as I am any judge of these things. He often sang a line from a song: “I’ll forget many things in my lifetime, but I’ll never forget you.” (Jim Reeves, 1962) It seemed strangely apt; we played the song at his funeral.