Walk a million years in her shoes

Cutting edge simulations are making Lucy walk again to help figure out the evolution of humanity's ability to run

THE evolutionary journey is a long one. We don't know where it will take us, but we can certainly look back and contemplate the road travelled.

For the vast majority of our time here on Earth we walked. No trains, plains and automobiles, not even a horse, just our own two feet. That's a hell of a lot of miles, over the millennia; our poor soles.

We've not always been Sapiens (some might say we're still not, really); early on in the journey we're more proto-human, but still we walked. It was our thing.

Sometimes we ran; okay, we probably ran a lot. It was a hungry Earth, and we were a tender morsel, for those with the teeth and claws, to make of us a treat. Eventually, we tamed fire, and got handy with the flint – suddenly we're the ones running after lunch. You might say, we've not stopped since.

But we're running away from ourselves, here; before we sprint off down a tangent, let's slow down and stroll back to the point.

An international team of scientists, led by experts from the University of Liverpool, have recently taken a fresh look at the running capabilities of an early human ancestor, Australopithecus afarensis.

The species is better known to us as 'Lucy', courtesy of the fossil that first alerted us to the bygone existence of these early hominids, when it was discovered in Hadar, Ethiopia, back in November 1974.

Fast forward back to the present; Karl Bates, professor of musculoskeletal biology at Liverpool University convened experts from across the UK and the Netherlands to use modern technology to explore the way Lucy moved, when she was alive all those millions of years ago.

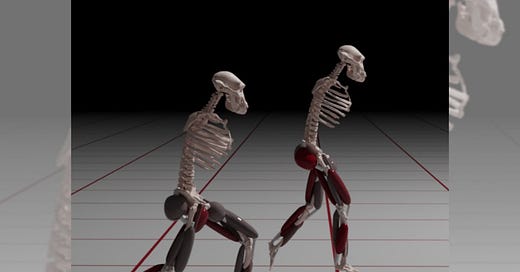

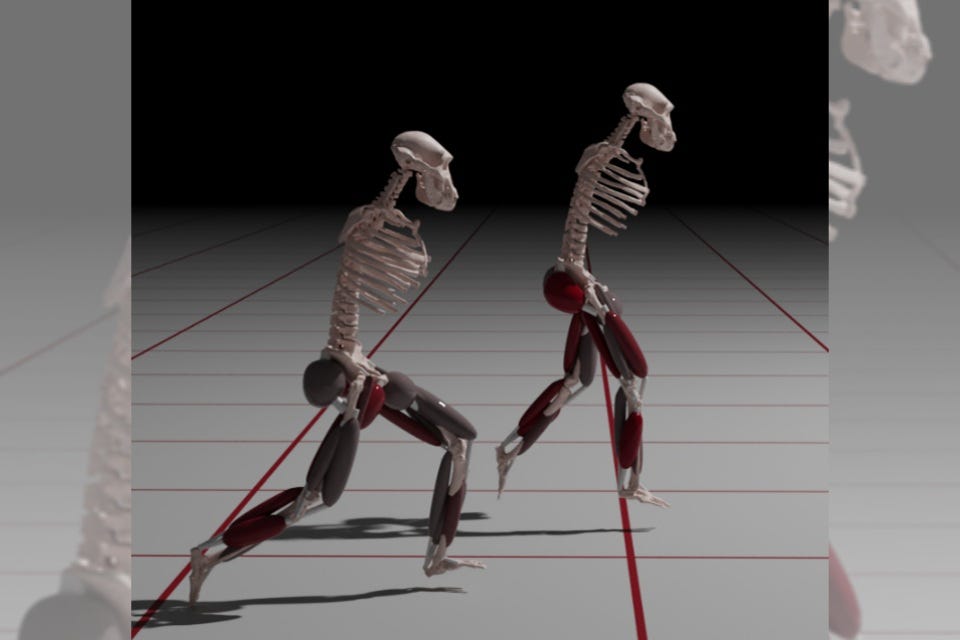

Together they used cutting-edge computer simulations to uncover how this ancient species ran, using a digital model of Lucy’s skeleton.

Running with the past

“When Lucy was discovered 50 years ago, it was by far the most complete skeleton of an early human ancestor,” Bates said. “Lucy is a fascinating fossil because it captures what you might call an intermediate stage in Homo sapiens’ evolution.

“Lucy bridges the gap between our more tree-dwelling ancestors and modern humans, who walk and run efficiently on two legs. By simulating running performance in Australopithecus and modern humans with computer models, we’ve been able to address questions about the evolution of running in our ancestors.

“For decades scientists have debated whether more economical walking ability or improved running performance was the primary factor that drove the evolution of many of distinctly human characteristics, such as longer legs and shorter arms, stronger leg bones and our arched feet. By illustrating how Australopithecus walked and ran, we have started to answer these questions.”

Previous work on the fossilized footprints of Australopithecus by multiple research teams has suggested that Lucy probably walked relatively upright, and much more like a human than a chimpanzee.

The team's new findings demonstrate that Lucy’s overall body shape limited running speed relative to modern humans, and therefore support the hypothesis that the human body evolved to improve running performance, with top speed being a more critical driver than previously thought.

The team used computer-based movement simulations to model the biomechanics and energetics of running in Australopithecus afarensis, alongside a model of a human.

In both the Australopithecus and human models, the team ran multiple simulations where various features thought to be important to modern human running, like larger leg muscles and a long Achilles Tendon, were added and removed, thereby digitally replaying evolutionary events to see how they impact running speed and energy use.

Digital evolution

Muscles and other soft tissues are not preserved in fossils, so palaeontologists don’t know how large Lucy’s leg muscles and other important parameters were. However, these new digital models varied the muscle properties from chimpanzee-like to human-like, producing a range of estimates for running speed and economy.

According to the team, the simulations reveal that while Lucy was capable of running upright on both legs, her maximum speeds were significantly slower than those of modern humans. In fact, even the fastest speed the team predicted for Lucy (in a model with very human-like muscles) remained relatively modest at just 11mph (18kph).

This is much slower than elite human sprinters, who reach peak speeds of more than 20mph (38kph). The models show the range of intermediate (‘jogging’) speeds that animals use to run longer distances (‘endurance running’) was also very restricted. The team says this perhaps suggests that Australopithecus didn’t engage in the kind of long-distance hunting activities thought to be important to the earliest humans.

“Our results highlight the importance of muscle anatomy and body proportions in the development of running ability,” Bates added. “Skeletal strength doesn’t seem to have been a limiting factor, but evolutionary changes to muscles and tendons played a major role in enhancing running speed and economy.

“As the 50th anniversary of Lucy’s discovery is celebrated, this study not only sheds new light on her capabilities but also underscores how far modern science has come in unravelling the story of human evolution..”

The study, Running performance in Australopithecus afarensis was published in the journal, Current Biology.

So, when we're running for that train, or jogging in the park, maybe we should spare a thought for Lucy; she took a leap so we, her descendants, could hit the ground running.

MC

Lucy. There goes my religion lol