When it’s too dark to read, you need a little light

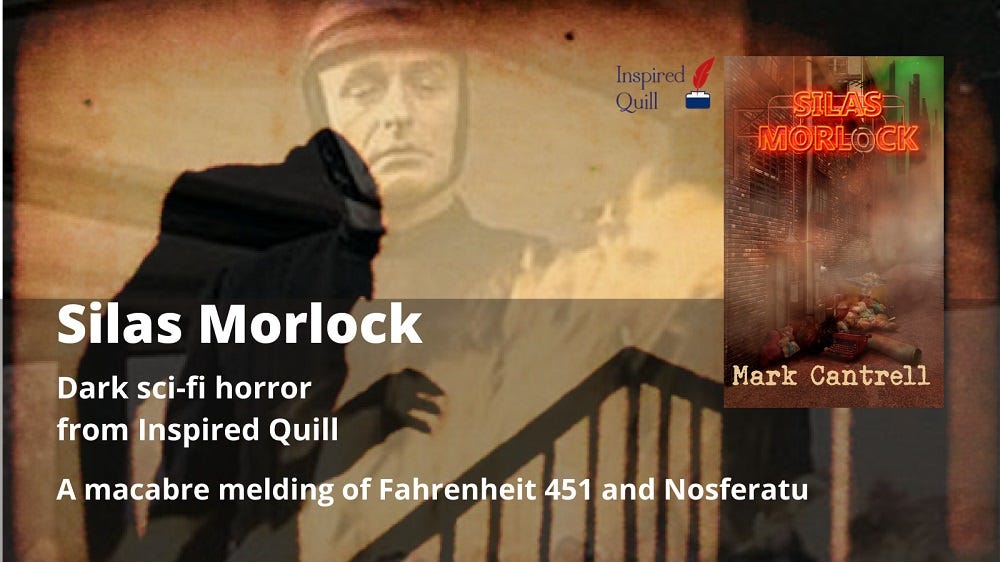

Silas Morlock: In this macabre urban horror, humanity is haunted by the ghost of its literary past

A macabre urban horror set in a world without books, Silas Morlock offers a homage to the power of literature, so the novel offers the perfect excuse to take liberties with some playful cultural references

THERE’S a lot of literary allusions at play in the novel Silas Morlock. Some are perhaps less obvious than others, starting right there with the title, but if you’re going to write a homage to the spirit of literature you might as well let your hair down a little.

First, we’ve got the unmistakable reference to the subterranean beasties in H G Wells’s The Time Machine (1895), but it also doubles up as an oblique reference to Silas Marner (1861) by George Elliot.

The why of the morlocks is dealt with in the book, as to the second, well that was more a case of – why not? It scored both the title and the title character. Of course, Silas Morlock couldn’t be further removed from the life and times of a simple linen weaver, but that’s literature for you.

Not all of the allusions in the book are deliberate, I confess; some of them are in there for the hell of it, but plenty more were chosen because they seemed apt at the time. Doubtless, there’s a few more in there that slipped past unnoticed as the words on the pages flurried into being.

There was no missing out on the opportunity to borrow a little Tolkien for the section heading: And in the Darkness Find Them. No prizes for guessing (correctly) this paraphrases a line from The Lord of the Rings concerning Sauron’s One ring to find them all, and in the darkness bind them.

A similar stunt in the third section offers a nod to Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker, with the heading: For the Book is the Life (for the blood is the life), but the novel also draws on historical references too.

Caxton, for instance, is named for William Caxton, the man cited as using the first printing press in England. It also happens to be his real surname (he never did tell me his first). Then there’s Elzevir, the librarian, whose historical pseudonym harks back to a family of 17th Century Dutch booksellers, publishers and printers.

Every burned book enlightens the world

Both of them are members of the Incunabula, an underground organisation that seeks to preserve and protect humanity’s cultural legacy. This is a time of persecution, where the artefacts of human creativity risk being erased on the pyres of a new ‘dark age’. These subversive few strive to secure some kind of legacy for the future – but they’re playing a dangerous game with fire.

Primarily, we’re talking books here, but in its secret libraries buried deep beneath the macabre city of Terapolis, the Incunabula also hoards a trove of musical media, films and television, even digital relics such as computer games, as well as photographic archives and other artforms.

Silas Morlock is available in both paperback and digital editions. Order it via any good bookshop, but if you want to support a vibrant small press publishing scene, then please do consider buying direct from the publisher, Inspired Quill.

Further information and links are available on Mark Cantrell, Author.

The word itself – incunabula (plural) – harks back to the early days of the printed book in Europe. It refers to those printed before the year 1501 and takes its meaning from the Latin for ‘cradle’. In that respect, the organisation depicted in Silas Morlock ‘cradles’ or ‘swaddles’ books (and other cultural artefacts) in its protective embrace.

So, what other references and allusions do we have to play with? Well here’s a few you might ponder (in no particular order):

The character Dorian: a reference to The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1890) by Oscar Wilde. Again, it’s an alias

The character Maus (and his tattoos) is a reference to the graphic novel of that name by Art Spiegelman (1980/1991). No formal alias, this, just a nickname

Luca and his red hi-vis vest: it’s a Star Trek reference, you know – how the red shirts tend to end up dead? (Sorry, I couldn’t resist)

Gorsedd, the ruling council of the Incunabula, is not a literary allusion as such, but as it says in the novel: It was originally used in reference to a meeting of bards and druids prior to the annual eisteddfod in Wales.

The book Caxton grabs at random when he is visited by an agent of darkness is Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom The Bells Toll (1940). And the bells certainly do toll a dark portent

Tubeworms – the mass transit system in Terapolis: This isn’t a literary allusion, but a recollection of a video game me and a few mates played incessantly when hanging around the student union back in the day. Memory fades, but it was probably R-Type

C’roaches: The slang used here plays on a reference picked up from Naomi Klein’s No Logo (1999), where she claims that members of the advertising industry refer to consumers as ‘cockroaches’. Nice...

Purists may scowl at some of these allusions because in a strict sense they don’t all invoke literature, but other cultural mementoes, whether film, television, or even computer games.

Even so, they belong. Writing is present in so much of our cultural endeavours, after all: movies are built around scripts; so too is theatre and television drama. Computer games themselves are no stranger to the written element, especially in this day and age, so why not go a little ‘multimedia’ in the references?

Art-forms such as painting and sculpture, meanwhile, may not themselves involve words in their fashioning, but they evoke a response all the same that often generates reams and reams of words.

We are creatures that shape ourselves in story, after all: the Narrating Ape.

We do not always fashion our tales into words, but into objects and artefacts, too. Whatever the form of creative expression, we are sharing and exploring our understanding of ourselves – as individuals and as communities.

Narrating Ape

In a real sense, however fleeting it may be in the great scheme of things, we are declaring our presence as creatures with a rich inner life, capable of delving into the deep mysteries of existence, as much as the inherent absurdities of life and living.

This storytelling urge doesn’t have to be ‘high culture’, either; bullshitting with your mates down the pub is a part of it – maybe even a remnant of the root of it – as we share a yarn and bond. Story is a part of our social grooming, a manifestation of our nature as hyper-social animals.

In its way, Silas Morlock sets out to celebrate this spark of human creative expression. All those references and allusions are a part of that, a way to offer a little colour to the dark tones of a macabre tale.

The Narrating Ape yearns to tell stories, to bond through a sharing of expression; we lose a part of ourselves as individuals and as a species when that is taken away.

[Maybe something to bear in mind as we contemplate the emergence of AI-generated ‘culture’.]

The novel reflects this, and builds it into a curious tale of good versus evil – the root, you might say, of so much of our literature.

Strangely, perhaps, Silas Morlock’s companion, Bill, was never an intentional reference to a certain Shakespearean ‘meme’, even though the skull’s depiction surely cries out for some kind of ‘alas poor Yorick’ moment. The mind works in mysterious ways.

On that note, let’s leave with one last reference. This one really sits at the soul of the novel as it seeks to pay homage to our literary creativity. You may want to update the language for more modern, inclusive sensibilities, but here it is as uttered by Rudyard Kipling in a time and space since gone to dust.

“Words are, of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind,” he said.

Caxton, along with his co-conspirators in the Incunabula, are fighting to preserve this “powerful drug” for future generations, that it might some day open the doors of perception and usher humanity into the light beyond the dark times.

So say we all.

MC

First published on KoFi, 22 March 2022

Silas Morlock is available in both paperback and digital editions. Order it via any good bookshop, but if you want to support a vibrant small press publishing scene, then please do consider buying direct from the publisher, Inspired Quill.

Further information and links are available on Mark Cantrell, Author.